A MAN FROM THE BORDER

STOJAN PELKO

This text is an extended version of the introductory greeting before the lecture by the Croatian writer Miljenko Jergović entitled “What is the new reality today?” at the Goriška Cultural Centre on 6 March 2025.

How did Miljenko Jergović end up in the Goriška Cultural Center? Ugh, long story.

Once upon a time, more than twenty years ago, I wanted Miljenko to write a film script based on a poem by Ed Maajka Mahir and Alma, which would be directed by Jan Cvitkovič. It didn’t work, but Janov and Eda’s video succeeded Fuck you.

Sometime later, ten years ago, as part of our candidacy for the European Capital of Culture – only “ours” was Dubrovnik at the time – Miljenko would take over a bookstore on Stradun and offer books of his choice there for a month. We didn’t succeed because we were beaten by the River.

And in the third, six years ago, it went as follows: when Irwin’s framed portraits of Bosnian national heroes from the series Was ist kunst? were exhibited in Kostanjevica, we talked with Miran Mohar and Goran Milovanovic about how nice it would be if Miljenko, who wrote a wonderful column about the Banja Luka exhibition for Jutarnji list, came to Kostanjevica to tell who Valter was. who defended Sarajevo, which national heroine was the Imam’s daughter, and which hero ended up as an assistant to the commander of Goli Otok.

And it came—and it was unforgettable.

Last year, we listened to him with open mouths and teary eyes in Vilenica, when he received the award of the same name deep underground and explained that in these parts we always used to throw our neighbors into caves. Then we gave each other a hand to come to Gorizia.

And now we are here, in the Cultural Center … and it all came together. Let me explain what “everything” is.

Goran Milovanovič, director of the Božidar Jakc Gallery – Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Kostanjevica na Krki, suggested that at the scientific symposium on the occasion of the exhibition A Distant View Someone who is not an art historian, but who would rather outline the zeitgeist of the twenties and thirties of the twentieth century, would also speak. Jergović proved to be an exceptional choice: not only because he described in his oeuvre both key Sarajevo events that bordered the 20th century – the assassination of Crown Prince Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo in 1914 and the siege of Sarajevo in the Bosnian War after the breakup of Yugoslavia – but also because his novel First of all, we know that there were tigers in his family at home.

Goran first hosted us at the Kostanjevica exhibition in January – and because Miljenko liked her, he quickly agreed to be a speaker at the Novi Gorica symposium. In mid-February, fourteen beautiful pages of the author’s manuscript arrived from Zagreb – and we were able to start translating and preparing for the lecture. Even with Boris Peric, our good spirit of screenwriting residencies, we agreed to take the guest after the lecture to the Vecchio Gorizio to use the Dorcet Sardoč Fund to resurrect the memory of other tigers.

In short, if a person wants something intensely enough and does not give up after the first failure, in the end everything falls into place. That is why I am sincerely happy and proud that Miljenko is with us tonight.

But that’s not all. Where barely one ends, another story already begins.

By concluding one chapter of the official programme of the European Capital of Culture with a fascinating intertwining of social history and family story, Jergović is also opening another: he is the first in a series of lecturers of the year-round Festival of Complexity.

We have followed in the footsteps of the Ljubljana manifesto of in-depth reading, premiered at the Frankfurt Book Fair two years ago, when Slovenia was the guest of honour – and we are building a series of those heroes and heroines who do not stop at the surface, but dig deep below the surface, the collective and the individual; which counter the dictates of one-liners with long subordinates, the media sound-beat with the melody of the author’s script, and the algorithm of social media with the logarithms of progressive, critical thought. That is why this year Miljenko Jergović will be followed by Didier Eribon, Slavoj Žižek, Ilija Trojanow, Kapka Kasabova, Antonio Scuratti … and many others.

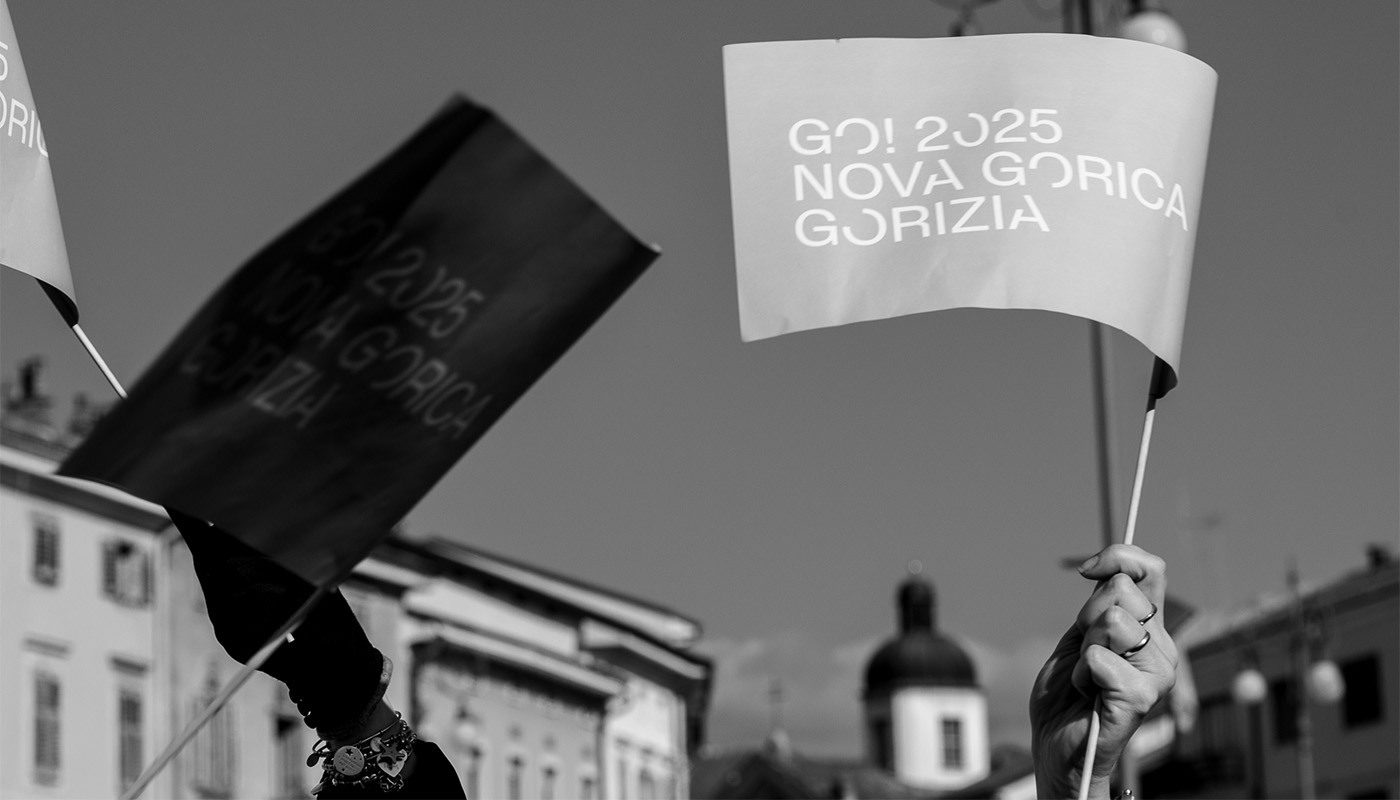

This brings us to an even deeper intertwining of the two projects of the official GO! 2025. In the preface to the exhibition catalogue, director Milovanovič wrote that in all these years the programme and vision of the Kostanjevica Museum had been built in the spirit of Srečko Kosovel’s thoughts: »Let us not be limited in time and place. Our cultural life must be in line with European cultural aspirations.” And indeed, in the network of institutions and cities that Kostanjevica na Krki brought to Kostanjevica in Nova Gorica with the symposium, there are many European capitals of culture: Rijeka, Graz, Pecs, Maribor, Novi Sad, and finally Nova Gorica and Chemnitz.

Why do we need to associate like-minded people today – and why is the tragic memory of a bygone era necessarily linked to a dramatic insight into the present? The first indent in the historical table, which hangs in the open corridor between two rooms at the exhibition in Kostanjevica, and can be found in the catalogue at the end, under the title “The World of 1925”, is as follows: “Jan. 3. Mussolini establishes dictatorial power.” And just a paragraph below: “February 14: Rehabilitation of the Nazi Party in Bavaria.” The former is still an honorary citizen of Gorizia, and in Chemnitz is the Alternative for Germany reached nearly 33 percent. So we still have a lot to talk about if we want to talk realistically about the new reality in Europe … and the world.

And why did we go across the border, from Nova to Stara Gorica, to Jergović’s lecture? Because those few of us who had the privilege of reading his text before we heard it live knew how it ended. This is how Miljenko Jergović concludes his narrative:

“If today, in the spring of 2025, my Nono and our uncle Berti from Ravnikarjeva and Tito’s Nova Gorica were to walk towards Gorizia, step by step, we would both definitely go home to our family. And if then, on the same day or the next, my Nono and our uncle Berti from Gorizia were to walk again, step by step, towards Nova Gorica, they would certainly both go home again to their own. It means to be a man from the border. Then the house exists only as long as you approach it; as long as your Other remains behind your back. And this has been our new reality for a hundred years.”