KLEMENT OF THE SOUTH AND HIS FALL INTO ETERNITY

written by MARKO KLAVORA

“Carelessly exposing my life to the forces of nature gives me back a double life and strength so that the fickle crowd cannot swallow me up. My heart is then accessible only to the will to work and love.” (Klement Jug, 1922)

Alpinist and philosopher Klement Jug (1898–1924) was born in Solkan and belongs to a generation that experienced the First World War and the changes that followed it in its youth, two periods that operated with completely different dynamics. I find this important to point out, as I try to look at Klement’s life and that of his contemporaries through the perspective of these changes, especially through the gap between the two “times”, the First World War.

When Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary on 23 May 1915, Klement was not yet seventeen years old. He completed the fourth year of the Imperial Royal State Gymnasium in Gorizia. He continued his education in Ljubljana, while the rest of the family remained in Solkan, as the Italian shellfire was not yet so frequent. Klement’s diary entries reveal the hardship he was going through, as his surroundings perceived him as hostile and unnecessary in the difficult war conditions. This probably explains his attitude towards Ljubljana and its citizens, in contrast to the simpler, but also healthier environment along the Soča River in his native Solkan. He writes in his diary: ” I would have gone to the Ljubljanica if the water had not been so dirty, but I wanted the Soča so much, the love of home, and the whole of Ljubljana did not seem worth my sacrifice.”

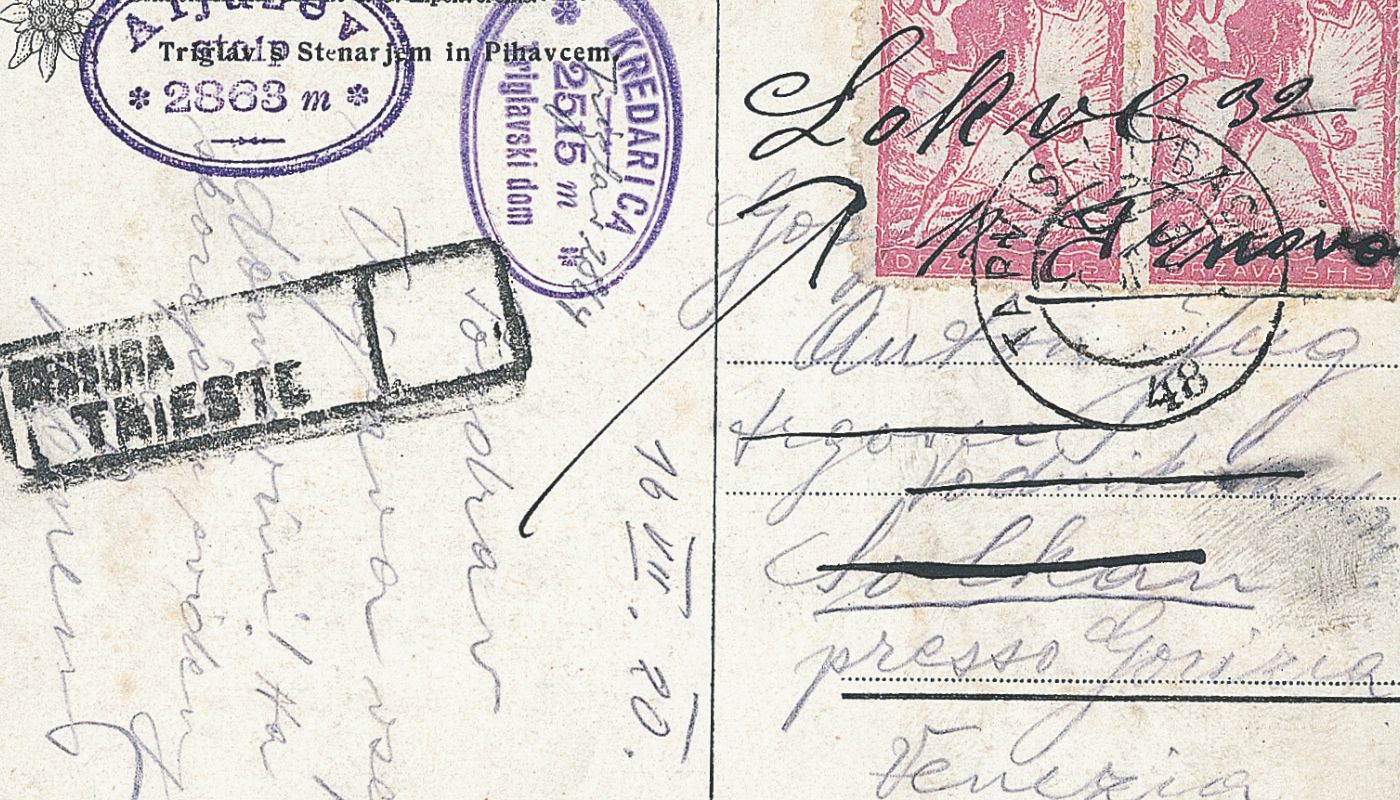

On February 12, 1917, he finished the sixth grade of high school early, and then immediately went to the military, as a one-year volunteer private (and later corporal) in the 27th Regional Defense Infantry Regiment. He successfully completed the eighth grade of the state high school on July 5, 1919. Perhaps the best description of that time and atmosphere is the back of his certificate, where the day after his graduation, Klement affixed two stamps, of the then no longer existing State of SHS, depicting a man who had freed himself from his shackles. [1] Klement added: ” In freedom”. However, he was a citizen of the Kingdom of Italy, since the Austrian Littoral was assigned to the Kingdom of Italy according to the London Agreement of 1915. He decided to continue his studies in Ljubljana. He enrolled in philosophy and natural sciences.

He was shaped and matured during the war, but it also left him with doubts about man and humanity. Consequently, also about himself and his role in the world. He wanted to serve the nation. But which nation? This was no longer the idealistic vision from the days of the Gorizia grammar school. The experience of a refugee on home soil is still too vivid and bitter. Now he is again a kind of refugee in his own homeland, because if he wants to get from Solkan to Ljubljana, he has to cross the state border, which has cut off approximately a quarter of the Slovenian national territory.

A 21-year-old young man was desperately searching for an Archimedean point to help him understand the world and himself. He found mountains.

He was first taken to the mountains by his university classmate and friend Zorko Jelinčič, who later became one of the leaders of the Slovenian illegal anti-fascist organization TIGR. The year 1922 was a turning point in his mountaineering career. In January, he completed a winter hike to Grintovec, which he later described and sent to the editor of Planinski vestnik. This was the beginning of his mountaineering writing, or rather: his upbringing. The same year, he also joined the Skala Tourist Club. The club was founded by bold young men who were dissatisfied with the ossification of the already established SPD [2] , which at that time was mainly concerned with administrative and economic matters. His descriptions of mountaineering tours in Planinski vestnik became extremely popular, especially among young people. Through these writings, his attitude towards mountaineering activities crystallized as he described the tours, which became increasingly demanding in the summer of 1923. As in other areas, he knew no compromises or retreats. If you decide to do something, you have to follow through. Boldness, self-control, and physical conditioning, all of this is said to have extraordinary educational power. But all of it was guided by his will, which was the will to win, to be the champion.

He climbed practically only two seasons: in the summer of 1923 and the summer of 1924 until the accident on the North Triglav Wall on August 11, 1924. During this time, he climbed alone or with fellow climbers, most of whom were even younger than him, and he became a role model for them.

During the May Day holidays in 1921, Jug began a love affair with a teacher, Milka Urbančič. Since they later lived in different places, they began to correspond, and by the time of Jug’s death in 1924, there were over 700 letters. She was a teacher in Šempeter pri Gorici in 1921, and it is not difficult to imagine how he first saw her during his study holidays and stared into her “dreamy eyes”. Milka was the chosen one, the only one worthy of the concept of love that he developed in his ethics. Shortly afterwards, he wrote to her: “Mountains are like women: you cannot love them unless you find resistance in them. Only when you subdue them do they become dear to you, and the dearer the more sacrifices they have demanded of you… And once you have mastered them through all obstacles with your honest and strong will, it seems to you that they have also come to love you and that they trust your responsible self-confidence.«

In a sense, a project that failed him because of its utopianism and steadfastness. In May 1924, he visited her in Otlica, where she worked as a teacher, where he found her in a village inn in the company of carabinieri and a teacher. Why did an incident in Otlica, which seems so innocent to us today, throw him off track so much? His pride was stung by the fact that his girlfriend was hanging out with Italians, and even more so, with Italian soldiers – carabinieri and teachers – who, as representatives of a foreign power, were not only conquering and building on the peaks of the (Slovenian) coastal hills, but were also conquering their (Slovenian) girls. At this time, fascist pressure was extremely intense, and through the so-called Gentile reform, this was most reflected in the Slovenian community precisely in primary education, in the area where Milka worked.

And although he did not want to, he was now at the point where he had been when he entered university: “The stars are grinding and the mud is swallowing them,” he wrote in a letter to Milka. With the difference that he now had a developed concept of material ethics. Therefore, he could not and did not want to give in at any price. He simply

On July 16, 1924, he illegally crossed the border between the Kingdom of Italy and the Kingdom of SHS for the last time. That same day, he was in Aljažev dom. His last mountaineering notes and letters show us the great determination with which he undertook new exploits, which were even more demanding and dangerous than the year before. He wrote postcards to his climbing companions and arranged them in a military manner, who would climb with him and on which day.

On August 11, he had a fatal accident while “searching for connections in the Triglav Wall from the path across Prag to the right in the pitch darkness to the Bamberg path.” After a hundred-meter fall, he died on the spot.

Klement Jug was buried on August 17, 1924 in Dovje near Mojstrana in a small village cemetery. The parish priest of Dovje, Jakob Aljaž, wrote the cause of death in the obituary: “fell 100 meters from the north face of Triglav and killed himself, found dead on the 15th.” 8. from comrades Skalashev, academics and gunsmiths.[3] What the Dovšče parish priest, a symbol and elder of Slovenian mountaineering, thought about Klement, his climbing exploits and the younger generation of alpinists is best illustrated by an excerpt from a newspaper article he wrote the same day Klement was found and sent to the newspaper Slovenec: »The undersigned adds my personal opinion: ‘Omne nimium nocet’ – do not exaggerate – do whatever is right. This should also apply to tourism. [4]

Professor France Veber, his best friend and classmate Zorko Jelinčič, and his university colleague Vladimir Bartol played the greatest roles in transmitting Klement’s tradition, at least in the initial period. Each from his own perspective: Veber as a teacher – a scientist, Bartol as a classmate – an envious admirer, and Jelinčič primarily as a grieving friend, mountaineer, anti-fascist. They have largely shaped the image we have of him today. However, this image is in many places a mirror of their personalities and lives and not of Klement’s life and thinking: Veber evokes the imagination of Klement the philosopher, Jelinčič the myth of Klement the anti-fascist, Bartol in his short stories the myth of the mysterious demonic tester of wills.

However, in my opinion, the writer from the Primorje region, Alojz Rebula, came closest to the tragic life (and death) of Klement Jug: “Yes, Truth and Woman, both with a capital letter, both were sought by the young heart, until in the end it cried out deceived like a man who comes across a dead man! […] Only lonely ravens will perceive the waving of hands in the void and the silent fall of a body and the impact into the damp abyss and the silence again leveled…”

—————–

Sources and literature

[1] “Chainsaw”, a regular postage stamp of the State of SHS, issued in 1919. The image of a slave tearing off chains was designed by Ivan Vavpotič and expresses the feelings of the vast majority of Slovenes upon the transition from the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy to the State of SHS and, a month later, to the Kingdom of SHS.

[2] Slovenian Mountaineering Association, op. a.

[3] PANG, ZKJ, Klement Jug, obituary.

[4] Jakob Aljaž, Third accident on Triglav this year, Slovenec, 16. 8. 1924.