IN THE WORLD OF “DYSTOPIA” WE ARE LOSING TOUCH WITH REALITY

written by KARLO NANUT

The conference drew inspiration from the multilingual and multinational identity of the cross-border ‘twin cities’ of Nova Gorica and Gorizia, and returned to the idea at the heart of the pan-European Eurozine project: translation as a means of shaping cross-border public space. If we want to understand the Other directly, completely and flawlessly, it is almost certainly an unrealizable dream that can turn into a totalitarian and dystopian illusion, she said. American historian Marci Shore in her lecture on a dystopian world .

Everything is translation, ”alles ist Übertragung”. This German expression has a broader meaning, all human communication is translation. The words we translate are transferred from one language to another and we become a means of putting into words someone else’s voice. We allow others to own us. But there is no such thing as a perfect translation, just as there is no such thing as a perfect metaphor or a perfect simile. T Such an endeavor, while seemingly well-intentioned, quickly becomes a utopian illusion. Historically and theoretically, attempts to fully understand or harmonize with the Other have often given rise to forms of moralizing control that end in oppressive or dystopian outcomes. Research addresses why this dynamic repeats itself and how alternative approaches to relationality can prevent such dangers. Humans have a natural tendency to understand, especially in contexts of interpersonal differences. Many philosophical and political traditions view understanding between people as the foundation of peace or justice. However, the desire for a complete, flawless understanding of the Other implies complete transparency of his or her motives, desires, beliefs, and experiences. Attempting to fully understand the Other is therefore both impossible and dangerous, as it often leads to utopian fantasies that can transform into totalitarian or dystopian forms of control. The ‘‘Other’’ designates individuals or groups that we perceive as different from ourselves.

In phenomenology (e.g. Husserl, Levinas), the ”Other” is essentially indecomposable, a bearer of difference that resists complete explanation. The encounter with the Other is always an encounter with some radical opposite. The Other is always on the other side of a border that we will never finally cross. The French philosopher Paul Ricoeur spoke of the formation of one’s own identity as a path of openness to the Other. Today, however, identity is presented as the ”thug self”, as an absolute ruler. The uniqueness of the Other is disrupted by the constant circulation of information and capital. But where only the positivity of the self is encouraged, life is impoverished and new pathologies appear: the inflation of the entrepreneurial self, personal relationships give way to ”electronic” connections. Only the encounter with the Other, destabilizing and revitalizing, can grant each person their own identity. Attempts to understand the Other without remainder often lead to the fusion of difference into equality. Utopian projects strive for complete harmony, clarity or unity. When these ideals are transferred to interpersonal or social relationships, utopia implies the elimination of misunderstandings, conflicts, or ambiguity.

However, as thinkers such as Karl Popper, Hannah Arendt and Zygmunt Bauman have pointed out, utopian visions often justify coercive systems that are supposed to realize their ideals. A complete understanding of the Other would require complete access to subjective experience, which is epistemologically impossible. Human cognition is shaped by perspective, bias, language and context. Even the most genuine moments of empathy retain a certain degree of mystery. Despite these limits, societies have repeatedly fantasized about complete understanding: universal consensus, complete transparency or technologies that eliminate misunderstandings. Such visions promise harmony but require the elimination of ambiguity, difference and autonomy, conditions essential to freedom. The desire to fully know the Other can be transformed into systems of surveillance, ideological domination or psychological normalization. Totalitarian regimes have historically desired not only obedience but legibility: the elimination of private thought or distinguishable identity.

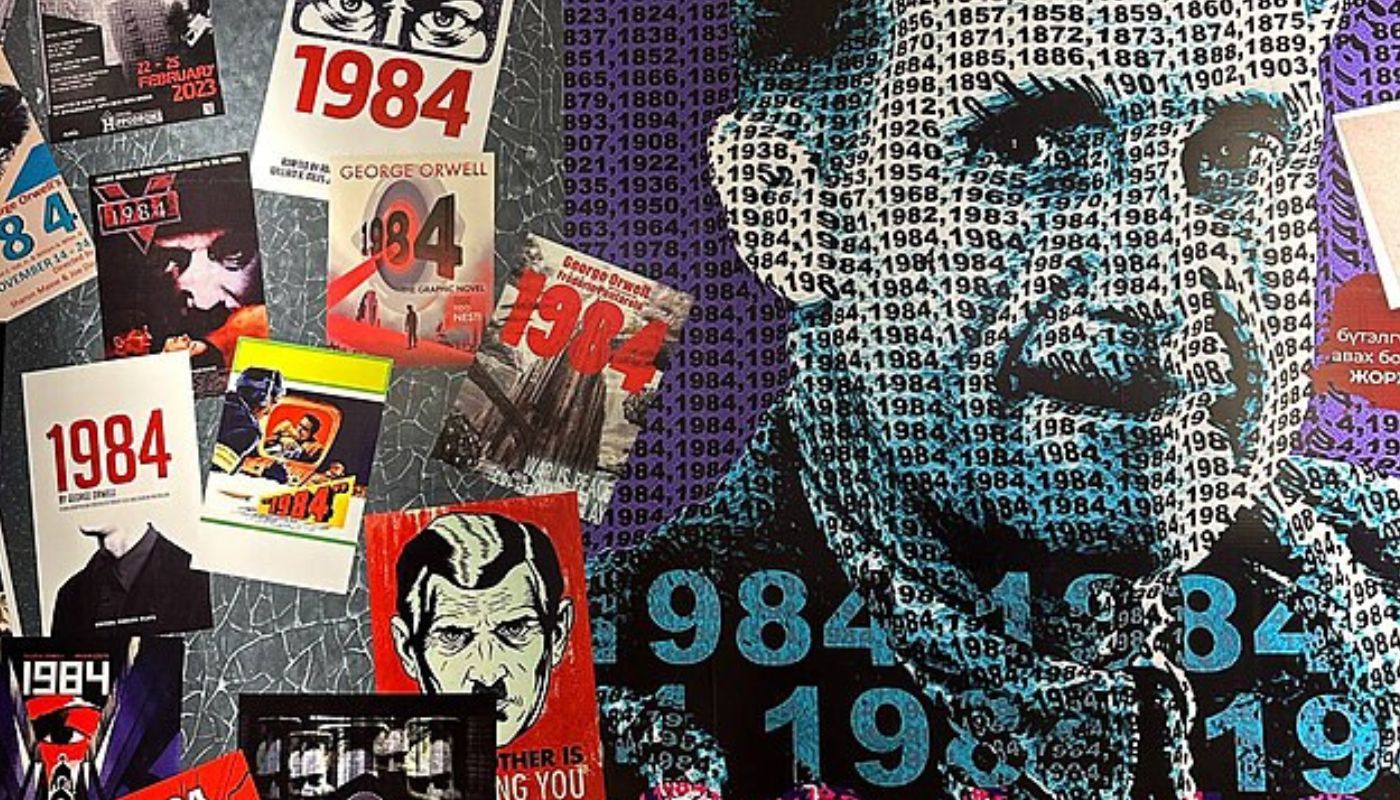

When the Other becomes fully known, it must also be simplified, categorized, or transformed to fit the framework of the knower. This process suppresses otherness. In extreme cases, it justifies assimilation or violence. Dystopian narratives, since Orwell 1984 to contemporary novels, show how ideas about a complete understanding of the Other become oppressive. Attempts to make each subject fully visible and explainable erase individuality, unpredictability, and disagreement. Philosophers like Levinas and Glissant advocate an ethics that respects the insoluble opacity of the Other. Understanding becomes a dialogue, not an act of mastery. Instead of striving for perfect understanding, pluralistic societies rely on partial understanding, negotiation, and difference, conditions that preserve freedom and prevent totalization. Empathy can remain a virtue if it acknowledges its limits. The awareness that we can never fully know the Other encourages humility, curiosity, and nonviolent forms of solidarity. The desire to understand the Other directly, completely, and without error is unrealistic and potentially dangerous.

Although motivated by a desire for harmony or unity, such efforts risk turning into utopian illusions that justify totalitarian forms of control. A sustainable and ethical approach to human difference requires acknowledging the limits of understanding, respecting inexplicable otherness, and cultivating relational practices that value complexity rather than eliminating difference. Accepting the impossibility of complete understanding can be the very condition for freedom, dignity, and authentic coexistence. The idea of exhausting ourselves for an ideal future does not lead us to the meaning of life: on the contrary, it risks making us even more disillusioned (as is happening now, especially for younger generations). The charm and dream of a perfect world ultimately degrades our life in this world. Films like The Matrix have effectively translated the virtual power of this illusion into the language of its digital simulation. It is not good to want to build an ideal future that does not exist. It is better to re-invigorate the world and the life that does.