GORIZIA IN COMICS

by MIRT KOMEL

If I think back to my childhood, when I read Mickey Mouse in Italian, thanks to which I learned the language — together of course with the Italian transpositions of the legendary Japanese cartoons of the eighties — or to my adolescence, when I moved on to more serious comics such as Dylan Dog or Nathan Never, not even in my wildest dreams would I have imagined that one day I would see my city in my favorite comics.

But the impossible became possible during the summer of this year, when, on the occasion of the European Capital of Culture in Gorizia, a special episode on Mickey Mouse no. 3626 and a special edition of Nathan Never in two parts, namely no. 409 and 410, was released. However, as with unconscious desires – let me call them that – their realization does not correspond to the reality of what one would have expected, both in terms of deficiency and excess. In fact, the difference in approaches and in the way in which the historical opportunity for Gorizia is seized in these two comics could not be greater, because in one case — Mickey Mouse — we are faced with a complete absence of reality, in the other — Nathan Never — with an excess of reality, which, however, only in this case does not make the question either more intriguing or less problematic.

Mickey Mouse no. 3626 contains, as always, several independent stories, including the one entitled

The plot, as always with Mickey Mouse, is simple: the protagonists Here, Quo, Qua (in the original English Huey, Dewey, Louie) led by Skopušnik (in the original Scrooge McDuck, in the Italian version Uncle Scrooge) set off in search of a treasure hidden in the castle of Gorizia, which once belonged to a countess. The company of ducks sets off and the mysterious traces they find in the castle and the castle district lead them through Rastello Street to Travnik, passing through a fleeting view of various palaces to the Transalpine Square, aka Europe Square, where the “border between Italy and Slovenia” is located. At this point, however, the protagonists are “too tired to continue” (I quote the comic), so they go back to the city. Yes, that’s right. No mention of Nova Gorica, let alone crossing the border, the only Slovenians in the comic are unrecognizable silhouettes in the only cartoon in which the Nova Gorica railway station is represented. Worse still, on the last page, when the mystery of the castle has already been solved, Uncle Scrooge says that they still have time to “visit the city” (we have a city to visit), which is then emphatically repeated in the final dialogue: “You mean the city of Gorizia, tion?

This is not an oversight, but a deliberate ignorance, which plays into the hands not only of the dominant Italian ideology, which despises everything Slovene, but also of the excessive emphasis on the past, that is, on everything Yugoslavian and “Titoist” — but also of a certain particular agenda of the Italian partners of the European capital of culture in Gorizia. In fact, the owner is Nova Gorica,

Here we are, in short, dealing with a very planned ideological ignorance, which spreads faster than the Covid-19 pandemic, since its repercussions can also be read on the websites of Slovenian national television, for example in the article by journalist Alessandro Martegani, who in his contribution on Mickey Mouse No. 3626 — entitled “The issue of Mickey Mouse dedicated to the European Capital of Culture has been snapped up on newsstands in FVG” and with the significant subtitle “The story, included in issue 3626 of the famous comic magazine, is set in Gorizia and offers many iconic places in the Isonzo capital” — writes that it is “an original way to make the cultural heritage of the two Gorizias known through the language of comics”, indeed, “a way of celebrating the European Capital of Culture and fixing in time this experience that has united the two cities even more”. It is bizarre that even this journalist — like Mickey Mouse — does not mention Nova Gorica at all, but absorbs it into the “two Gorizias”, united into one, that is, the (“old”) Gorizia, which demonstrates the last ghost of the fascist ideology with which we are dealing here: the union of the two Gorizias, yes, but “again” in Italian.

In a completely different way, the idea of the “two Gorizias” is addressed by Nathan Never 409-410 with the titles Arrestate Nathan Never and The Mystery of Aquilea, as conceived by the screenwriter Bepi Vigna and the illustrator Romeo Toffanetti, a duo that in the past has already distinguished itself with the Trieste edition of the same comic, also in two parts, The Windy City and Check Point 23.

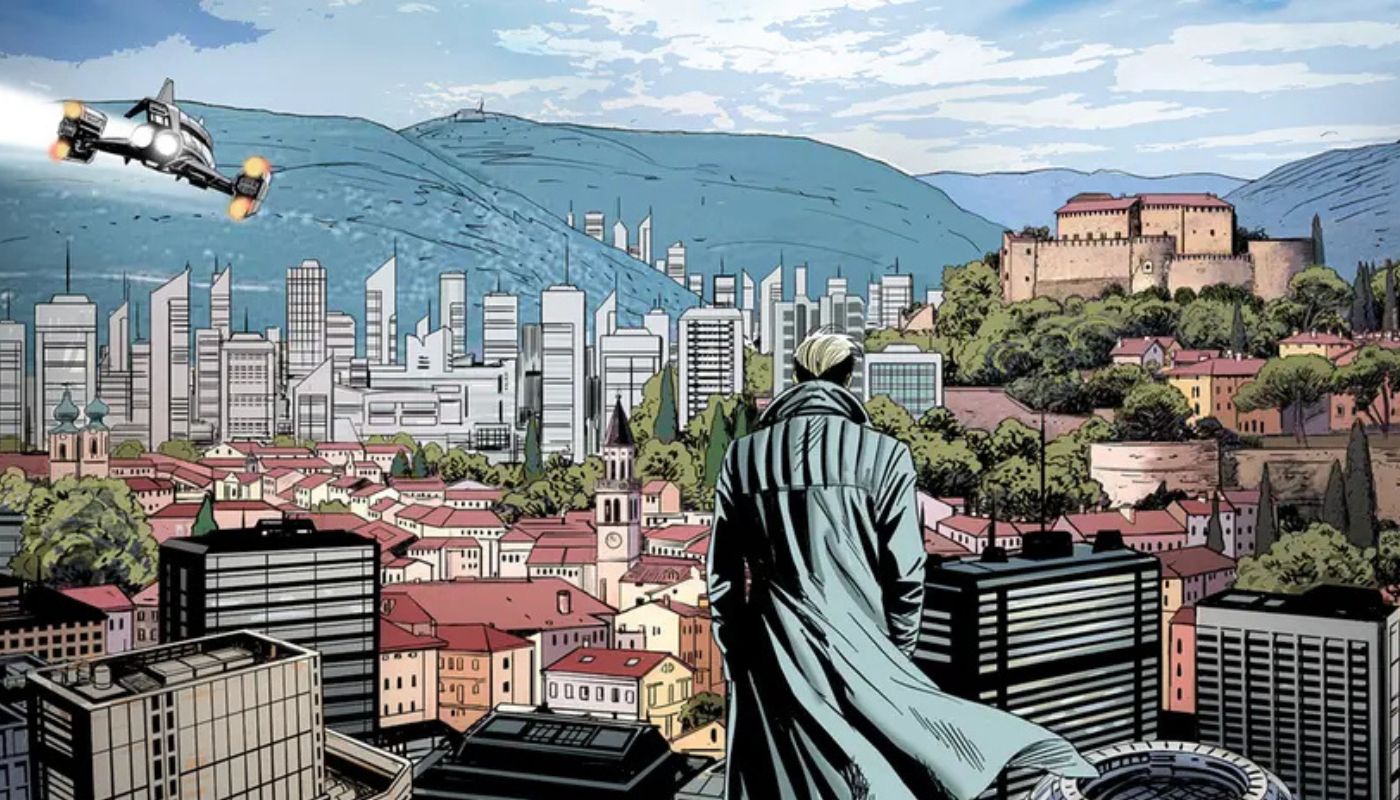

I must admit that I am biased, at least in this respect, because thanks to a series of happy literary coincidences I met Romeo, who showed me a preview of his splendid illustrations for the Nathan Never in Gorizia, where I was literally fascinated by the futuristic vision of Gorizia and in particular of Nova Gorica, with iconic places such as the castle, the station, the co-cathedral, the Solkan bridge. With an equivalent representation of both Gorizias, united in a science fiction idea – in the emphatic sense of all three words – post-apocalyptic Protectorate, administratively governed by the Priory of Gorizia, this double Nathan Never is undoubtedly an exceptional aesthetic surpassing, which fills precisely that gap that I tried to illustrate above.

Starting from the beginning of the story in Piazza Europa — more precisely at the railway station, where, as we see, even in the distant future trains are still late — with the following spatial location: “Old Europe, Eastern protectorate. Nova Gorica, border station”. On the border, but no longer on the border between Italy and Slovenia, but on the border of the Protectorate with neighboring countries, where the “protected zone”, reminiscent of the

Now, if I move from the description of aesthetics to the conceptual transcription of id(eologia), then we must first grasp the geopolitical idea of the “Protectorate”, which includes the triangle Trieste-Gorizia-Ljubljana (one could say a little jokingly and a little seriously “TIGLJ”): unlike the historical alternative actually possible in the post-war period between Ljubljana and Trieste, here as the capital of the Protectorate it is proposed… Gorizia (and in this same joking sense we could say that the Protectorate realizes the millenary dream expressed in the famous saying: “Trieste is ours, Gorizia will still be”). But what capital is it really? The two Gorizia are called “Nova Gorica” and “

At the head of the Protectorate there is the Priory, to understand it it is necessary to move from the real historical contexts to the narrative history of the world of comics Nathan Never, which only in recent times is acquiring a coherent and canonical image. Previously, in fact, every author who tried his hand at a script for a comic interpreted the pre-apocalyptic world in his own way, while now the story seems to be the following: humanity, in search of alternative energy sources, has dug into the very heart of the earth, literally causing tectonic shifts at a global level, so that world civilization has managed to save itself only at the price of retraditionalization, when the leadership of the Holy Roman Church rose to the Wayan Agung of Bali (!) as Gregory XVIII (!!), who conceived a “terrestrial federation” with the aim of space colonization, thus becoming known as “the Father of our age”. Hence the political power of the monastic Priory of history and its “administrative power” over the entire geopolitical triangle Trieste-Gorizia-Ljubljana.

The strength of the comic thus also reveals its weak point: although the “old” Gorizia is symbolically absorbed by the “new” Gorizia, on an imaginary level the two Gorizias are politically ‘united’ only under the religious mantle of the Priory, which draws its power from the “Name of the Father”, the paradox is never more evident than from the headquarters located in the castle of Gorizia, from where the gaze of the Great Other can embrace and, so to speak, touch both cities.

To conclude, I would like to mention an interesting point of contact, namely that also in the case of Nathan Never, as previously in Mickey Mouse, the plot is centered on the “secret treasure”, the narrative “MacGuffin”, which also emphasizes the historical past of the place in question.

Now, to be clear, I will return for a moment to the Lacanian: the agalma or “secret treasure”, which is “inside”, has a very specific function, namely to allow the creation of “a subject that is presumed to know” — in the case of this comic strip none other than the figure of Jesus Christ, since it is the “Holy Grail”, the chalice of the Last Supper, reinterpreted as an otherworldly artifact — where the emphasis is placed precisely on that “presupposes” that sustains fantasy, that is, the interweaving between the imaginary and symbolic registers that constitutes our perception of reality as a single whole.

The fantasy of the One, which we are talking about in our case, is obviously the fantasy of the “single city”, which is actually supported by the entire ideological apparatus of the European capital of culture, while in Mickey Mouse we can recognize the fascist version of unification (both Gorizia as “One city, Gorizia“) and in Nathan Never the liberal one (the autonomous Protectorate, within which the religious Priory is based in the castle and therefore on the border between Nova Gorica and the New City of Gorizia).

What is essential, however, is what is “repressed”, that is, the unitary signifier, the signifier-lord, which is absent, but which precisely because it is “repressed” returns in this or that guise of the “return of the Real”: in the case of Mickey Mouse, it is none other than Nova Gorica itself, which is the “lord” in this sense, as it is de jure promoter of the GO! EPK2025, while Gorizia is “only” de facto partner; in the case of Nathan Never, the repressed master is not the “Father of our age”, as one might think, nor Jesus Christ (both explicitly mentioned in the comic), but none other than Josip Broz Tito, who, significantly, is no longer on the Sabotin of the future.

The fascist and liberal aestheticization of politics must be answered, in short, in the manner of Benjamin, with the socialist politicization of aesthetics: the Gorizia of the future must be socialist, otherwise it will sink into barbarism. And even if socialism seems to some, at best, just a utopian “dream of the future” – or, at worst, a “dream of the past” – we can still see with our own eyes the current fascist liberalism in our dystopian reality.